Annie Dillard’s classic nature memoir, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, takes us deep into the wilds of Virginia – and our own imaginations.

Even before I have seen the pictures of Tinker Creek I’ve conjured this place in my mind’s eye: the steel-grey Roanoke River winding through the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains; the sycamores bending and dancing over the water’s surface; the ponds quivering with the footfall of invisible insects; the heat distilling the utterly foreign scents of a northern hemisphere summer, and the seasonal change crystallising them, imperceptibly, into the hard-edged frosts of winter.

All books are travel books, in this sense – or at least they should be; they exist to transport the reader to some place geographically or emotionally distant from their own, setting them on a journey that will expand their horizons and leave them transformed.

This is the charm worked on me by Annie Dillard’s 1974 classic, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, which had sat unread on my bookshelf for several years and whose portal I finally slipped through while locked down in my Sydney suburb during a second wave of COVID. Unable to travel further than 5km from my front door, I took the metaphorical journey to Virginia instead, with Dillard as my guide. This bible of nature writing is regarded by many as a foil for Henry Thoreau’s Walden – itself a transportive classic in which the writer ruminates on his two years spent living simply at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts.

Plunging into the valley

Though I’ve visited Massachusetts and a number of other US states (some, it must be said, fleetingly), I’ve never set foot in Virginia. And yet I’ve been drawn to this mid-Atlantic state in the country’s south-east by tales from an aunt who lived there when I was a child, and people I’ve met in adulthood: the year before the pandemic hit, a dear friend moved to Virginia from New Jersey; at almost the same time, while travelling in the Arctic, I met a delightful couple from that state’s capital.

“Do come and visit!” they’d said, with what I took to be classic Virginian hospitality.

And most surely I would have heeded their invitation, if things had been different. Instead, I take the book from my shelf and wade vicariously into the sassafras and ivy mangling the valley whose four seasons Dillard recorded when she lived here for a year in 1971, in a house “clamped to the side” of the valley. At the bottom of her garden ran Tinker Creek, the laboratory for her explorations and seasonal experiment. In this semi-rural setting she recorded sightings of muskrats floating along the river on their backs, praying mantises excreting their egg cases, bright orioles fading into the leaves, and – in the most brutally memorable of her observations – a bullfrog sucked dry by a giant water-bug (the image of deflated frog-skin stays with me for a long time after).

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard. Photo: HarperCollins

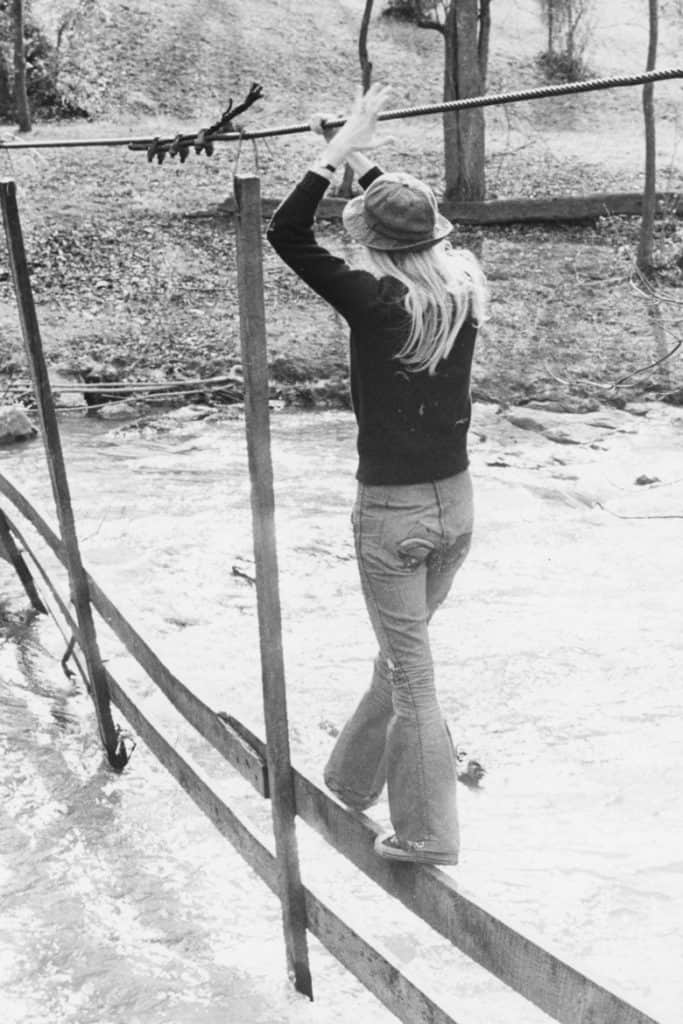

The writer Annie Dillard at Tinker Creek. Photo: Hollins University – Visit Virginia’s Blue Ridge

A copperhead snake’s no match for a mosquito

This is a deeply philosophical work in which Dillard evokes a microscopic world decades before the advances of science and Google and Wikipedia are well-developed enough to bore their own viewfinders into it. The telescope retracts from the particular to the general as I journey through a world conjured in minute perfection on the page; my view scopes from larvae and algae and insect casings and a mosquito biting a copperhead (isn’t this quite something?) to the wild and sweeping landscapes which contain these natural phenomena: the Allegheny and Blue Ridge ranges rising up on either side of the mighty Shenandoah Valley, and the rolling hills of the piedmont region. Google Maps help me travel further, to the eastern swathe of the state where the crumpled topography gradually smooths and flattens out into a sandy coastal plain and terminates on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. Street View deposits me in the very place I hope to alight upon in reality one day.

And the enlargement of the world proceeds further still, for it’s in the very distillation of this microcosm that exists in one spidery tributary of the Roanoke River that Dillard is able to imagine a broader world of which I am, in fact, familiar. The past, as she notes, “inserts a finger into the skin of the present and pulls”. And so we sojourn in other places, deep inside memories these few square miles of Tinker Creek evoke in her.

Tinker Ridge, Virginia. Photo: Jennifer Griffin Photography, Visit VBR

Hiking to Hay Rock, Roanoke. Photo: Jennifer Griffin Photography, Visit VBR

To the Amazon and Antarctica and beyond

“Piranha fish live in the lakes, and electric eels,” she writes of the Napo River in Ecuador, an inky, inscrutable Amazonian expanse along which I, too, have paddled. “I dangled my fingers in the water, figuring it would be worth it.”

In Antarctica, she notes, the explorer Paul Siple documented the scars adorning most adult crab-eater seals, evidence of attempted attacks by killer whales; they bring to mind the seal of this exact species I observed stalking, in its turn, an emperor penguin that had blown off course in Antarctica. The hunted was miraculously still living.

“How many crab-eater seals can one killer whale miss in a lifetime?” Dillard asks.

Her tales of caribou struggling “across the tundra from the spruce-fir forests of the south” recall my own journey to Norway’s Arctic (where I’d met that lovely couple from Virginia) and Russia’s Yamal Peninsula, where I’d camped with Nenets reindeer herders – a people whose culture and traditions are so similar to those of the Inuit (Eskimo) Dillard evokes so well. Across this vast tundra I’d shadowed the men as they lassoed a female, gave thanks for her life, and slaughtered her for sustenance. She, too, was one of those “old and unmated does” lamented by Dillard, singled out for her infertility.

Our roaming imagination

At face value, this pilgrimage occurs within a modest radius of the writer’s regional Virginian home; it is a metaphysical undertaking rather than a territorially ranging journey. But in my restless, wandering mind – constrained, remember, by a pandemic – Dillard’s pen telescopes incessantly back and forth, alternatively enlarging and foreshortening the view, unreeling the world for me as though it were a movie.

As it nears its 50th birthday, this Pulitzer Prize-winning work is still in wide (and much-adored) circulation. Perhaps its popularity stems from its ability to transport us, to provoke us into imagining a world both infinitesimally larger and far smaller than we are – though our average size, when taken with all living creatures, is little more than that of a house fly, Dillard informs us. It’s a book that gives our imaginations permission to roam wild and unbounded, and yet simultaneously forces us to focus. TTW

Feature image: Jennifer Griffin Photography – Visit VBR. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard is available from the Book Depository. Tinker Creek is located in the Roanoke Valley, at the southern edge of the Shenandoah Valley in the Blue Ridge Mountains; Virginia Tourism offers comprehensive advice for travellers to the region. Whet your appetite with these Virginian recipes.