They were the unlikeliest of heroes, yet they helped topple a hated regime. Their memory lives on in a fascinating museum of the Romanian revolution.

On December 16, 1989, out of the blue, protests broke out in the city of Timisoara in what was to be the start of the Romanian revolution. The next day the army was called in: shots were fired on the protesters, there were casualties, and all hell broke loose. The uprising soon spread to other cities. By December 22, the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife, Elena, had to flee Bucharest by helicopter, but did not get very far and were captured. On Christmas Day they were executed by firing squad, although fierce fighting continued in the capital for days afterwards.

I was working in the newsroom of The Daily Telegraph in Sydney at the time. Everyone there – the news journalists, sports reporters, page designers, the trainees – crowded round our televisions, watching the street fighting on the news bulletins, agog and in awe of the bravery of the people. Of all the revolutions that took place in Europe in 1989 – a momentous period in history – the Romanian was the bloodiest, and the only one in which the leader was ousted violently. By most counts, 1104 people were killed and more than 3000 were injured, the majority of them in the fighting in Bucharest.

Fast forward more than two decades, I’m on my way Romania. I have a blog on Romance languages (Romanian is one) and have signed up for a language course in Transylvania, Romania’s most attractive region, brimming with beautiful mountain forests and well preserved historic cities. It’s pretty central, and easy to get to. In contrast, Timisoara is more remote: it’s the capital of the Banat, which is flatter and regarded as less scenic. Nevertheless I want to make Timisoara my first port of call, even though it means going out of my way. I feel my journey should begin where the revolution began: in the city that played such a pivotal part in making Romania what it is today. Maybe my understanding of the country will be greater if I do it this way.

So, after breakfast on my first full day there, armed with a map from the city’s main tourist information office, I set off in search of the Muzeul Revolutiei – the 1989 Revolution Memorial Museum. The city is basking in brilliant sunshine. I find it hard to believe I was in what was once Cold War-era forbidden territory: the other side of the Iron Curtain.

Wounds that won’t go away

It must have been an old map, for when I get to the address where the museum is supposed to be, it isn’t there. But there’s a notice saying it has moved, and to follow the signposts along the way. As if on a treasure hunt, I go from clue to clue, and soon find myself at Strada Oituz, number 2B. It’s a double-story mansion, solid but greatly in need of some tender loving care, set back in a barely tended garden.

When I enter, the young man at the door rushes me upstairs to the viewing room, where a documentary is about to be screened. There are about half a dozen visitors present – a couple of Germans, and an Italian-Romanian family. They’re surprised to be joined by one from as far away as Australia.

The film is introduced by the president of the Memorial Association, Gabriel Traian Orban, a man in his 70s who hobbles around with the help of a walking stick – he was shot in his left leg during the revolution. It was not, however, the deepest, most painful wound inflicted upon him. “His son was killed in the revolution,” the woman sitting next to me whispers as the black and white documentary flickers to life on the whiteboard that serves as a screen. Orban, who apparently put together the film, does not stay to watch. Its English title is translated as We Don’t Die! and over the next 15 minutes or so we see how people who don’t die, do die. It’s fascinating but depressing to watch. We troop out sombrely afterwards.

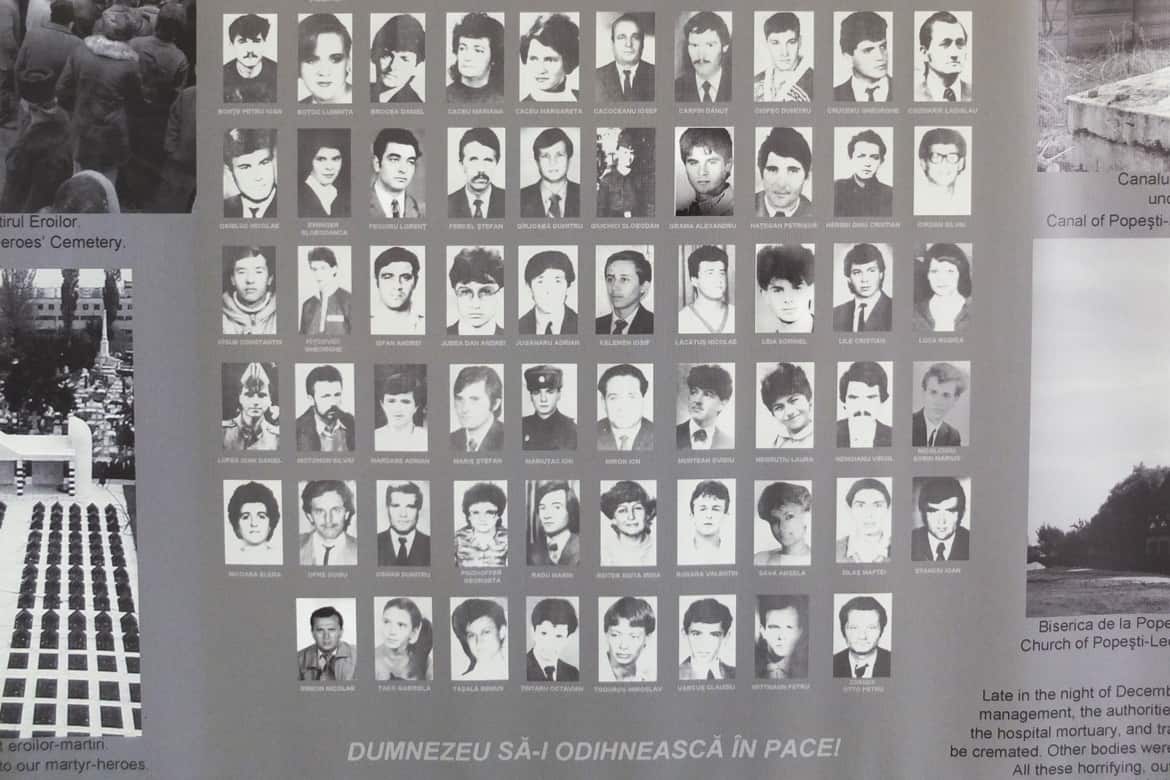

A display in the museum showing some of the civilians killed in the military reprisals.

Ordinary people in extraordinary times

In the museum’s corridors hangs a large banner with passport-style black and white photos of all the victims of the violence in Timisoara. They are a motley crew of the most unlikely looking revolutionaries: there’s a sanitation worker, a meat industry accountant, a writer and poet, a professor of music… Many are students with 1980s-style clothing, pimples and greasy mullets; some are simple factory workers, others retirees.

The first victim of the revolution was a pensioner, Rozalia Irma Popescu, crushed in the street by an armoured car at the age of 55; the youngest, Cristina Lungu, was shot in the heart, aged just two. The brief, matter of fact descriptions of each person’s fate make you want to know more, The 37-year-old nurse shot in the head at the children’s hospital while giving care to the wounded, for example. Was it a stray bullet? Was it a brutal execution, punishment for attending a revolutionary? In many cases, exactly who did what to whom that night will never be known. And there are people living today who don’t want it to be found out.

Exactly how many people died in Timisoara is not known. The uprising started out as a protest by the Hungarian minority against the eviction of their parish priest, Lazslo Tokes, who had spoken up for human rights, but the military’s heavy-handed reaction (people on the steps of the main orthodox cathedral were gunned down by snipers) sparked revolt. The military burned or disposed of some victims’ bodies and their remains have never been found. On its website, The Association of December 17, 1989, Timisoara, set up by the wounded and relatives of the dead, lists 101, plus 10 people from the city who died elsewhere.

Would any fighter pilot dare to bomb the packed square?

Thwarting the air force

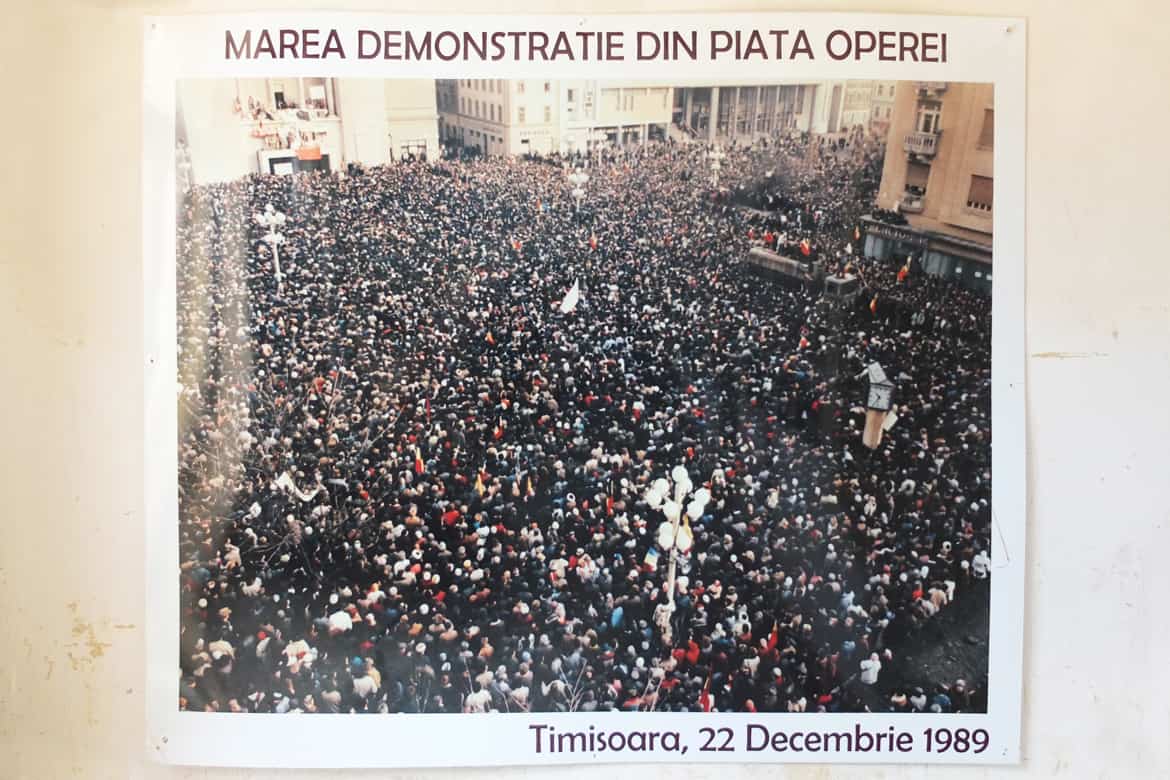

Posters in the museum show crowds packed in the city squares at the height of protest. In the largest square, Piata Operei in front of the opera house (it’s now called Piata Victoriei, or Victory Square), they are down on their knees praying. The woman who sat next to me in during the film comes over and, introducing herself as Cristina and who was a little girl in Timisoara at the time of the revolution, explains what is going on in the photo.

Rumours had spread round the city that Elena Ceausescu, who was in charge of the country while Nicolae was on a short visit to Iran, had ordered that Timisoara be bombed by the air force. The people of the city thought that if they jam-packed the square and went down on their knees in prayer, surely no air force pilot would have the heart to drop bombs on them (though with some regimes you never know), so they stayed there, huddled together in the icy December weather, for as long as they could.

The residents in the apartments alongside the square threw down chunks of bread and other bits of food to sustain them. Thankfully, the bombers never came.

The protesters cut out the communist coat of arms from the Romanian flag.

Humble heroes

The Memorial of the Revolution is a humble, simple museum – it’s privately run and has led a precarious existence financially – but that’s really the way it should be. Those who started the revolution, the “accidental heroes”, were humble people themselves. Their courage inspired people in other cities to take a stand, and events that happened in Bucharest and elsewhere are well covered in the museum.

Among the most moving pieces are the Romanian flags with the Communist Party emblem ripped out of the centre – the gaping holes, for me, a reminder of the void left by loved ones who died – and the miniature replicas of the dozen-odd sculptures that have been erected around the city in honour of the victims: among them The Target Man (his arms up, his chest bared like a target); The Martyrs (coffins piled on top of one another); and The Winner (a man with his left arm and leg missing, propped up by a crutch, his right arm raised in triumph).

Before leaving, I go to the main office to give my voluntary donation (the museum, being private, apparently cannot charge entry fees). Gabriel Orban is there. I tell him I’m a journalist and ask if he can spare the time for a chat, hoping he will tell me about himself, his son, and how the museum (which seems to be very much his baby) came about. He gives me a quick but penetrating stare, as if to trying to peer into my soul to unravel my motives. His own facial expression is inscrutable.

He shakes his head in refusal. “I am not so important,” he says.

I’m disappointed, but perhaps he is right. The ones are who are important are those who sacrificed their lives all those years ago; those whose absence is so painful for some, the dearly departed whose memory lives on, a ghostly presence inside the building.

I’m lucky. I’ve lived through a civil war but I’ve never been suppressed by a vile regime or been the victim of an atrocity. For those who risked their own lives so that others could live a better one, for all those who take a stand for the good of humanity when others do nothing, thank you. This is our little homage to you. TTW

Bernard O’Shea travelled to Timisoara at his own expense. Photos © Bernard O’Shea. Timisoara is a European Capital of Culture in 2023.