A long-dismissed culture offers timely, enduring lessons in the US capital.

If aliens were to land on the National Mall in Washington D.C. they could be forgiven for thinking that Homo sapiens is an intelligent species. For they’d be surrounded by what is probably the most impressive cluster of intellectual property on Earth. And monuments. The Ground Control guy in Houston greets this alien being whizzing through the transit zone: “Going to Washington D.C. eh? You’ll see a lot of monuments!”

Just look at the line-up on the 1.8km stretch of parkland between the Washington Monument and the US Capitol, bordered by Constitution Avenue to the north and Independence Avenue to the south:

- The National Museum of African American History and Culture

- The National Museum of American History

- The National Museum of Natural History

- The National Gallery of Art and the NGA Sculpture Garden

- The original Smithsonian building, known as the Castle

- The Freer and Sackler Galleries (dedicated mostly to Asian art)

- The National Museum of African Art

- The Arts and Industries Building (more at bottom)

- The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (dedicated to modern art)

- The National Air and Space Museum

- The National Museum of the American Indian

All of these bar the NGA are run by the Smithsonian Institution, which also has six other museums and the National Zoo in the wider Washington metropolitan area, plus two museums in New York. Entry to all is free, and the gardens surrounding the Smithsonian properties are “museums without walls” – designed to complement the knowledge within.

The museum has a prime view of the US Capitol.

Which one would you choose?

This particular alien, a member of the scribul cu urechi mari species (big-eared scribes), landed in the National Mall on a drizzly winter day. Luckily there wasn’t a riot taking place at the Capitol, otherwise he might not have been so impressed with the locals’ intellectual capacities!

Sadly, I had only one day to take in the sights. Just enough time for a walking tour in the morning (good for the body), and a museum in the afternoon (good for the brain and the stomach when in the cafeteria). Washington D.C. is certainly not a city you’d want to explore in a rush. But if you had only one day, time for only one museum, which one would you choose? According to the Smithsonian’s attendance figures for 2020, the National Museum of Natural History is by far the most popular. For many, it’s the obvious starting point. Our big-eared scribe, however, went for something different …

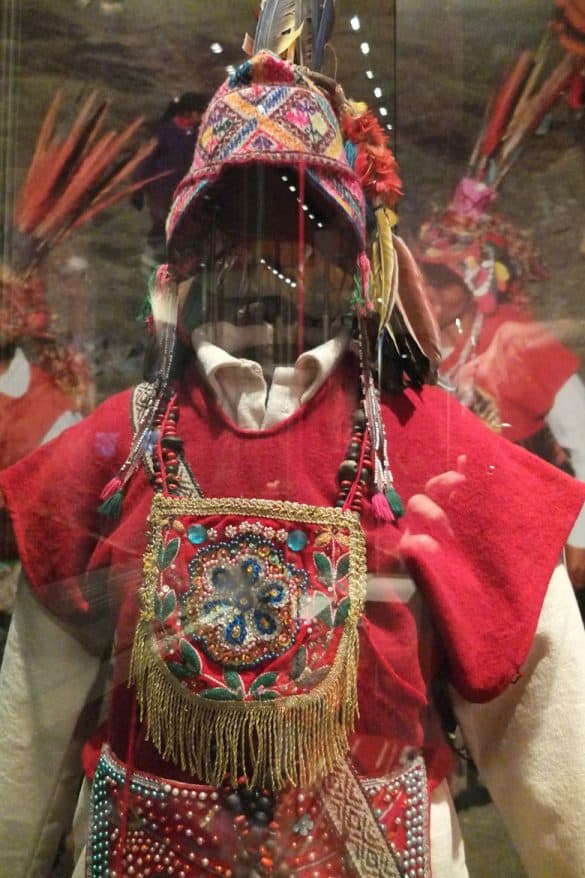

The museum has an eye-catching collection of ceremonial costumes.

The other side of the story

The top choice for me was The National Museum of the American Indian. Partly because I wanted to venture into the unknown. For too long, the stories of the world’s Indigenous people have not been properly told. When I was a kid, in the era of black and white television (we had to go to the cinema for splashes of colour), cowboys were the action heroes of the day. Cowboys and Indians. But the Indians were merely extras, a threatening menace circling vulnerable little houses on the prairie. They were there merely to be shot down, in enormous numbers until one of them became the last of the Mohicans. There was no political context, and never a sense of trespassing on their land. Now I wanted to know their side of the story.

I also wanted to learn more about their belief systems, philosophies and knowledge of the land – knowledge that the modern world, to its detriment, has too often mocked or dismissed as primitive, pagan or non-scientific. Now, we are coming to realise, modern humanity has been foolish in its ways, polluting the earth, our only source of nourishment. I wanted humbling simplicity and I wanted to be moved by it. And, in case you think I am being too morose, I’ll happily admit that I was hoping for a fun element: tribal costumes and art in all their colourful glory. I’m happy to say that the National Museum of the American Indian exceeded my expectations on all counts.

A vast collection

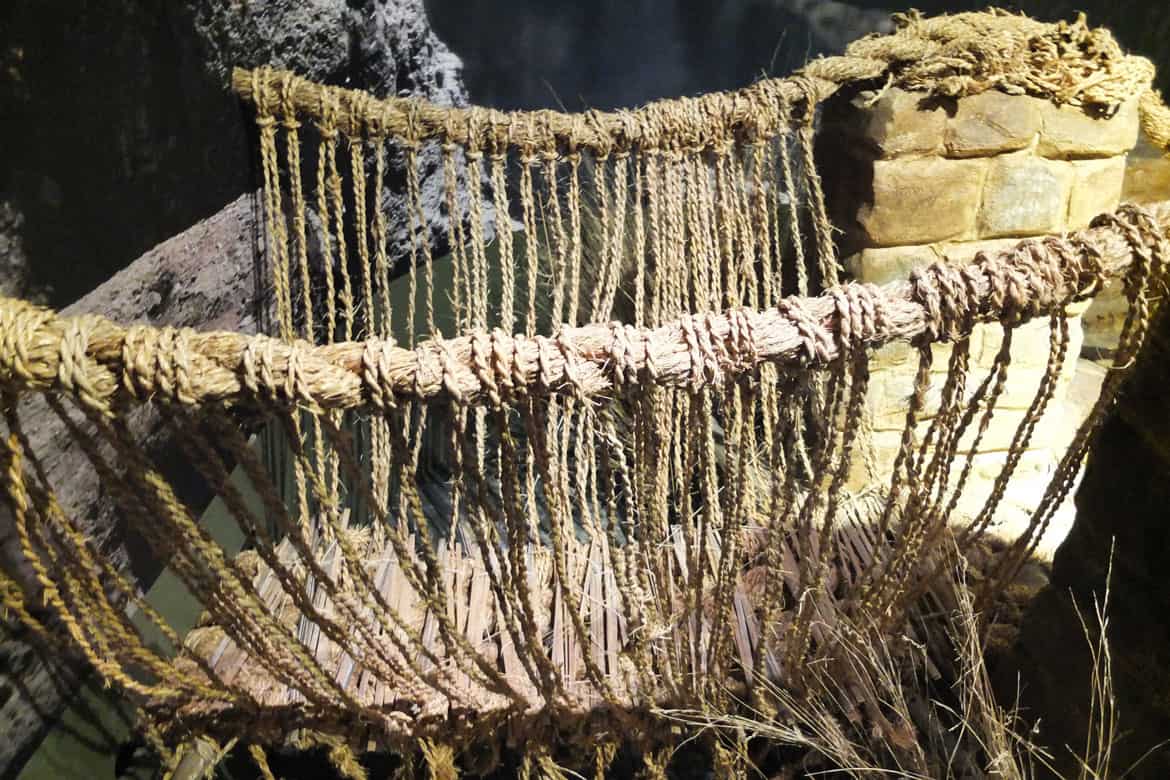

The museum opened in 2004 in an alluring, curvaceous building of golden limestone designed to look like natural rock formations sculpted by wind and soil erosion over the course of time. There are four levels open to the public, and it’s recommended you start at the top and work your way down. Together with its sister sites in New York and Maryland, it has “approximately 266,000 catalog records (825,000 items) representing over 12,000 years of history and more than 1200 indigenous cultures throughout the Americas”, plus more than 337,000 items in its photographic, media and paper archives. Not all can be displayed at one time, though.

The geographic distribution is impressive: “Approximately 68 percent of the object collections originate in the United States, with 3.5 percent from Canada, 10 percent from Mexico and Central America, 11 percent from South America, and 6 percent from the Caribbean. Overall, 55 percent of the collection is archaeological, 43 percent ethnographic, and 2 percent modern and contemporary arts.” You can view some of its exhibitions online here.

Acts of kindness

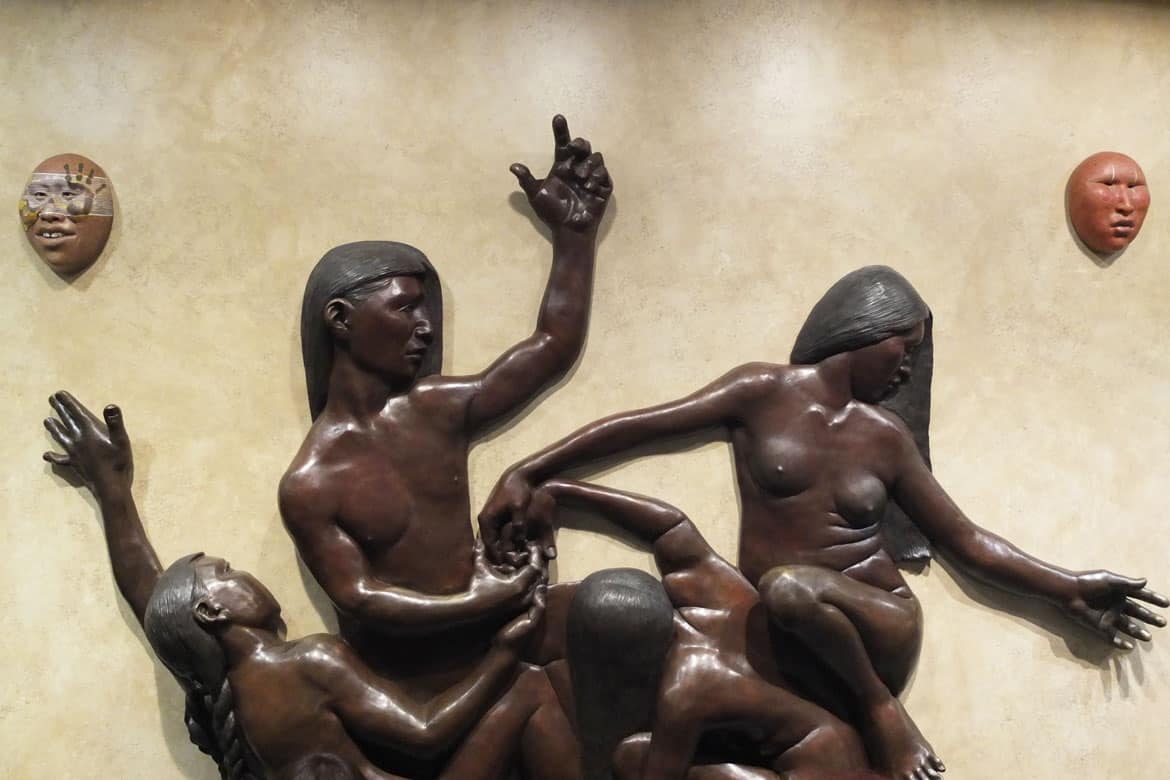

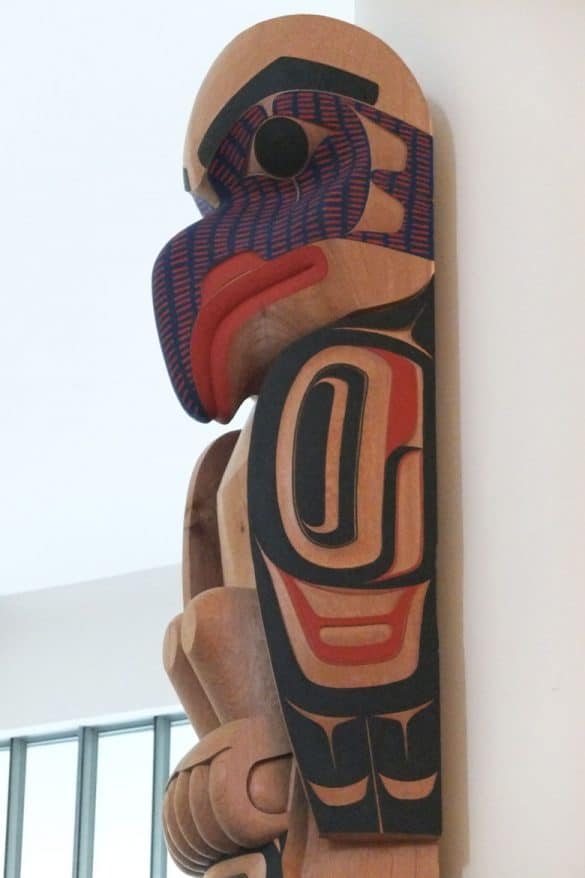

One of the most striking exhibits, Eagle and the Young Chief (pictured below) greets you in the foyer. Carved out of Western red cedar, by David Boxley (Tsimshian b. 1952) and his son David Robert Boxley (Tsimshian b. 1981), it tells a lovely story. A young Tsimshian man was walking on a shore when he spotted an eagle trapped in a fish net. He set it free, not knowing that it was a nax nox, or spirit guardian. Years later, the man, now the village chief, was walking along that same shore, in distress. The fishing season had been woeful and his people were starving. Then a live salmon fell from the sky. Looking up, he spotted an eagle flying away. Every day afterwards, the eagle brought the villagers food – not just salmon, porpoises too and even a whale! The eagle, a supernatural being, was repaying the young man for his kindness.

Be sure to walk round the building – the grounds are simulated wetlands. Among the shrubs there’s an imposing bronze statue, Buffalo Dancer II (pictured below), by George Rivera of the Pojoaque Pueblo community. For the Pueblo Indians, the Buffalo dance is “an enduring celebration, a prayer for the well-being of all”.

Lasting impressions

You can’t, of course, expect to gain anything more than a morsel of understanding of American Indian culture in a few hours at a museum, no matter how good that museum is. What you see is bound to be a neat, sanitised version anyway. How can you encapsulate years and years of heartache, political upheaval, bloodshed, the loss of your lands, the evaporation of your language and cultural identity and so much more into a museum exhibit anyway?

But if a museum can make everyone who walks in walk out a little older, wiser, sadder even, more thoughtful and respectful of all the people who make up the world we live in, it’s a job well done. For me, the National Museum of the American Indian filled in some of the gaps that had been missing in my childhood TV tales. Now it’s up to me to fill some more.

The Arts and Industries Building is set to reopen to the public.

Something futuristic to look forward to

The Arts and Industries Building, the Smithsonian’s second oldest, opened in 1881 as the first National Museum of The United States. Designed by architect Adolf Cluss, it was to be the permanent home for the exhibits of the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official World’s Fair to be held in the US (in Philadelphia). In the 1900s, its role evolved as some of its contents were transferred to new Smithsonian museums. By 2004, however, after suffering structural damage in a heavy snowstorm, the building had to close to the public. Renovations would cost a bomb, and its fate was left hanging in the balance.

But the story has a happy ending. From November this year (the Smithsonian’s 175th anniversary year) the Arts and Industries Building will reopen to the public with a new exhibition, FUTURES. Promising “a vast array of interactives, artworks, tech, and ideas that are glimpses into humanity’s next chapter”, the exhibition will run through to July 2022. TTW

Photographs: Bernard O’Shea. The writer flew to Washington D.C. courtesy of United Airlines. All travel and accommodation within the US was at his own expense.