The raindrops fall fat and heavy as Catherine Marshall weathers the first storm of the season in a bamboo-woven cheroot house on Myanmar’s Inle Lake.

I am smoking a cheroot somewhere on the vast and inscrutable Inle Lake when the dry season breaks. Fat raindrops announce themselves in ones and twos on the bamboo-leaf roof of the overwater house in which I sit. The droplets gather momentum and soon they have formed a crescendo above me. Smoke seeps from my mouth as I gaze out at the rain-dimpled lake: will my umbrella, until now a marvellous foil against the biting sun, protect me from this deluge?

My boatman thinks not: we shall wait out this unexpected storm, drinking the green tea offered to us in thimble-glasses, smoking the cheroots that are manufactured right here in this house.

Beside me, young women are rolling the traditional Burmese cigars, filling corn leaf sheaths with tobacco that’s been tempered with star anise and doused in a solution of rice wine, palm sugar, honey and tamarind. They gather the cheroots into bunches, secure them with elastic bands and place them inside lacquered cigar containers.

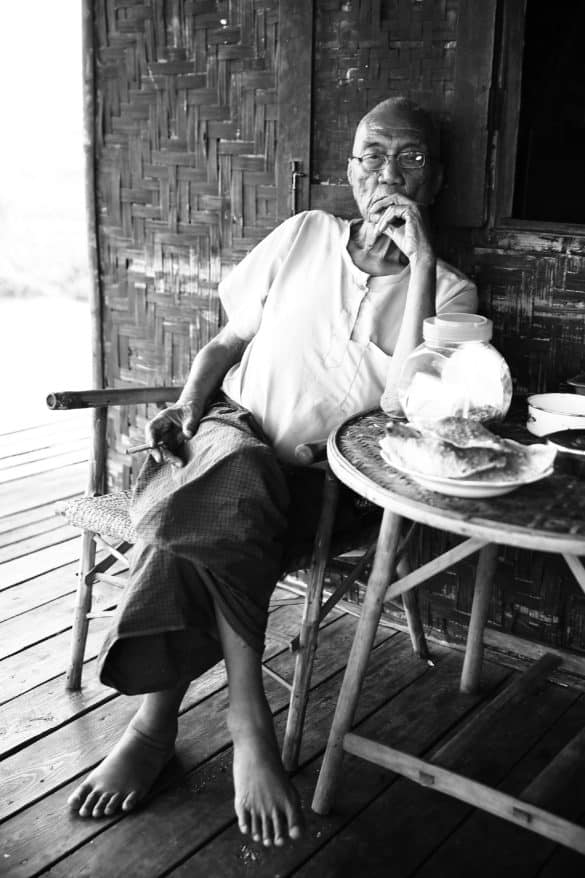

Outside, an old man is observing the storm, unmoved by this seasonal transformation. He raises a cheroot to his lips and a cloud of smoke blooms before him, obscuring the lines that are etched onto his face like a map. It is late April, and he is witnessing an early end to the suffering of this lake.

In the wet season, the monsoon will replenish the watershed that is rimmed by the Shan mountain range in Myanmar’s eastern Shan State. For now, the lake is shrunken and shallow, dribbling like a splash of mercury from Nyaung Shwe in the north to beyond the town of Pekon in the south. Parched as it is, you can drive for six hours and all the while have as your companion this body of endlessly shifting water, its surface dotted with coracles and floating markets and the houses that are elevated precariously above it.

A dense shroud of mist had been dancing on the lake’s surface when we rowed out to it earlier this morning. We’d advanced through the vapours under the power of a unique, one-legged rowing technique, employed in this instance by a man who had jumped onto the prow just as we pushed off from the jetty.

My base was the Inle Princess Resort, cushioned in acid-bright foliage and set at the edge of a canal that intersects the lake. Having guided us through thickets of hyacinth visible just beneath the water’s surface, the rower’s job was done; he sprang onto the steps of a stilted house and waved us goodbye.

Inle Lake lay before us, flat and shining in places where the sun had pushed through. The boatman revved his motor and suddenly we were flying across the tannin-rich water, our faces stung by its spray. All around us were the Shan mountains, watercolour imprints against a colourless sky.

The day had begun long ago for the lake dwellers, most of them Intha people who for centuries have lived on this lake and off its bounty. The women had set up their stalls at the floating markets, basket-loads of fish, fruit, vegetables, cheroots, clothing and silverware. The men had set off in their boats, casting shimmery nets as they rested their rowing leg on the oar, fishing with traditional conical nets, tending their floating crops, tethering their boats to poles in the deepest part of the lake before jumping in and trawling the watery depths for shrimp.

These were backdrop scenes, an ancient way of life broadcast like a gentle, rhythmic backing track as I explored the lake. The boatman took me to markets fringed by a crush of arriving and departing boats, silvermiths crafting reticulated fishes with rubies for eyes, and rickety stilt-houses where women wove cloth from the sticky threads of the lotus plant.

In the afternoon, as the sun burned down and rainclouds began to gather in the west, the boatman pulled up alongside Inthar Heritage House, originally built as a refuge for returned Burmese cats, which had become extinct in their own homeland. The house had since expanded to include a café and an aquarium filled with local fish species.

From the house I could see canals and organic gardens and rice paddies stretching outwards, water and soil merging seamlessly. The ingredients in my bowl of Shan soup came from this waterscape: mustard leaves, bean sprouts, tomato, chilli, coriander, fish sauce, sticky rice noodles. I drank Myanmar lager which made me sleepy in the heat and ordered pancakes with Shan forest honey for dessert. I could picture the beehives in forests of wild mango and acacia and flame trees, and those same forests cladding the Shan mountains which were bruised purple now in the late afternoon light.

Now the warm and radiant light is being erased by the first rains of the wet season, and those rains have trapped us in this bamboo-woven cheroot house suspended above the water. When the clouds have wrung themselves out we will climb into the boat and make our way back to the Inle Princess Resort on the far north-eastern side of the lake, beholding as we go the living gallery spread out before us: the floating crops anchored with towering bamboo poles; the pagoda glowing golden in the lake’s deep centre; the fishermen who are out here still, black silhouettes against a sea of shimmering silver. TTW

Catherine Marshall travelled to Inle Lake at her own expense. More information: Inle Princess Resort. Photos © Catherine Marshall.